The Jebel Khalid site

Overview

Jebel Khalid was a walled fortress town on a high limestone plateau overlooking the Euphrates river in northern Syria. It was founded in the early 3rd century BCE, when the Seleucid emperors were consolidating their hold on territories inherited from Alexander the Great. Its purpose may have been to control north-south river traffic and an east-west trade route. Its population, estimated in the range 4,500 – 7,500, seems to have included locals as well as Greeks. The site was abandoned around 70 BCE, when the Seleucid empire was collapsing. It was never resettled so it preserves its Hellenistic character.

The Australian Mission first surveyed the site in 1984. Excavation had to be suspended after the 2010 season.

Heather Jackson, 'Thirty years of work at Jebel-Khalid-on-the-Euphrates'. Syria. Ancient History - Modern Conflict Symposium, The University of Melbourne, Friday 11 August to Sunday 13 August, 2017. Audio recording with slides.

Location

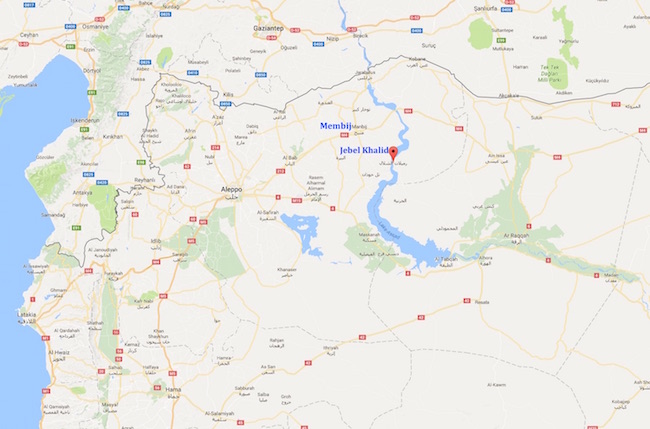

Jebel Khalid is on the west bank of the Euphrates, approximately 2 km south of the Tishrin dam. Just to the north is the village of Khirbet Khalid. On the opposite bank of the river is the village of Rumeilah.

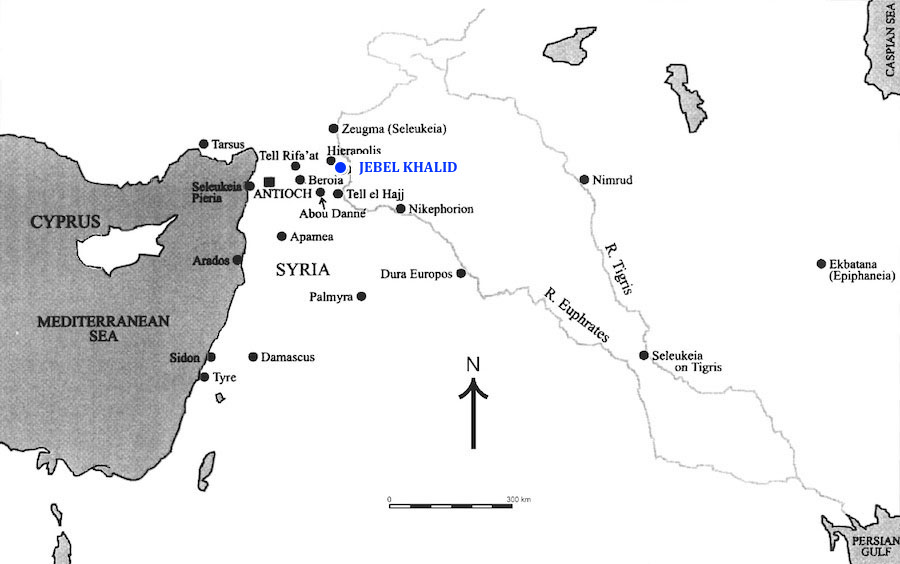

The nearest large city, about 30 km north-west of Jebel Khalid, is Membij (Manbij), with a population in 2004 of c. 100,000.

In Hellenistic times, Membij (ancient Bambyke) was refounded as Hierapolis:

Geomorphology

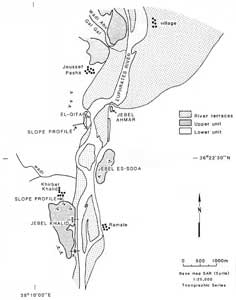

Following the main uplift of the region and regression of the sea in the late Pliocene, the area around Jebel Khalid has been dissected by wadis and rivers. Long slopes run towards the river. A plateau survives away from the river; it stretches westwards to Aleppo while to the east lie the higher plateaus of Mesopotamia. Nearer the river are isolated mesas. Terraces have developed along the wadis and the river.

Jebel Khalid is a mesa capped by hardened marine calcarenite, about 0.5 m. thick, with occasional pebbles of other material, deposited as the marine basin in northeastern Syria continued to subside during the Middle and Upper Eocene. Beneath this is a layer of white chalk, originally a lime mud. It is relatively easy to carve tombs and caves in this layer and to quarry stone blocks for construction, which have subsequently hardened.

The soil is generally thin and stony, with an average depth of 15-30 cm. It is typically silty to clay loam — probably remnants of an original red plateau soil left after erosion, with a younger layer of wind-deposited silty loam. The river terraces have more recent alluvial soil and in modern times, with irrigation, support various crops and fruit trees.

The area is semi-arid, with rainfall of 250 mm per year, mostly in winter. The mean temperature in January is about 5°C and in July about 30°C. In spring the landscape has a sparse cover of flowering plants and low bushes.

The Geomorphology sketch map was drawn before construction of the Tishreen Dam (1991-1999), when the river level varied seasonally by 1 to 6 m.

Topography

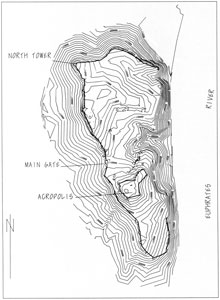

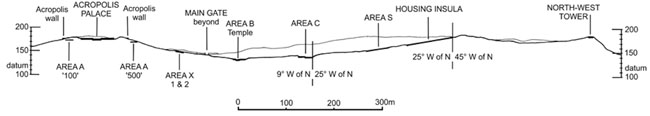

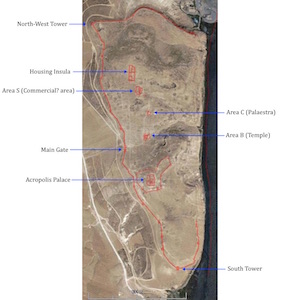

The Jebel Khalid mountain plateau forms a rough triangle about 1500 m along the river frontage, 600 m wide at its northern end, and 220 m wide at its southern end. Its sides at the north and for much of the eastern (river) flank are fiercely steep. From the south and the west the ascent is more moderate but the approach is long and totally visible.

The plateau rises to 427 m above sea-level; its highest point is about 130 m above the level of the river.

The plateau itself is difficult enough terrain, with two gullies and two lofty ridges.

-

From the south looking north to the southern end of the Jebel (centre), the North-West Tower (left) and the Tishrin dam (right) (B. Allardice, 2010). -

From the western wall looking south to the Acropolis. -

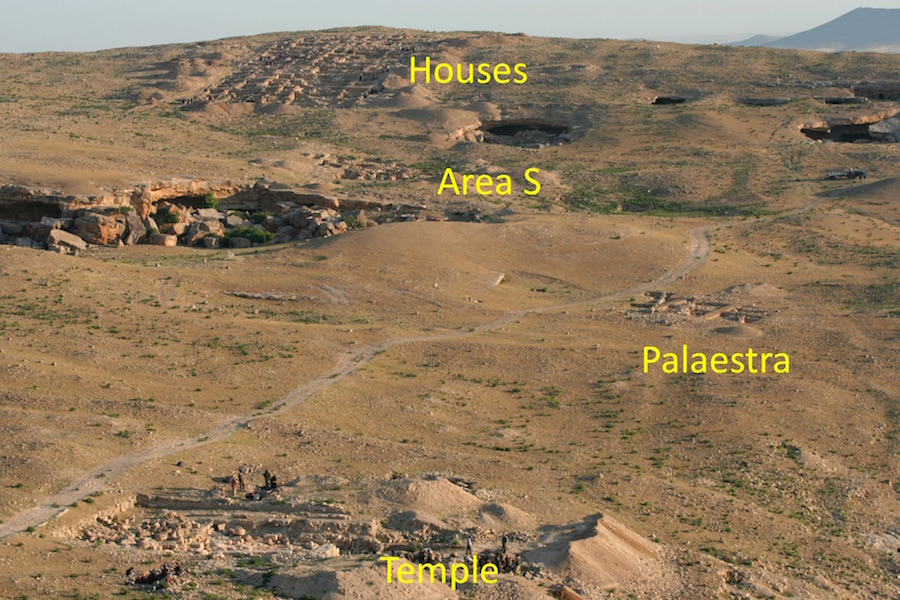

Areas of the site: from the Acropolis looking north, with the Euphrates on the right (H. Jackson). -

An on-site limestone quarry (B. Allardice, 2010).

Settlement history

Some 14 Iron-Age sherds recovered during survey are witness to users of Jebel Khalid prior to the Hellenistic Greek foundation. But no evidence has been unearthed of any earlier long-term habitation — though no doubt shepherds will have exploited the 50ha pasturage that the jebel offered in winter and spring.

The evidence of coins, ceramics and lamps all indicate that Jebel Khalid’s Hellenistic phase commenced early in the third century and lasted until the site’s peaceful abandonment in the 70s BCE.

Except for most of its eastern edge, where the steep ascent from the river presumably afforded enough protection, the plateau was protected by a fortification wall which keeps consistently to the highest point of land round the perimeter. The wall was about 2.8 m wide, 6 m high, 2.7 km in length, and included 21 towers and bastions. The Acropolis had its own wall about 0.7 km in length, with 9 towers.

The area enclosed by the perimeter wall is approximately 50 hectares. Limestone blocks for fortifications and buildings were quarried on-site. Major structures include a palace on the Acropolis, a temple, a palaestra, a commercial(?) area, and a block of houses (housing insula).

Squatter occupation certainly followed the site's abandonment, but not for long. The only area to continue in use was the Temple precinct until the Temple’s collapse in the second century CE.

Aerial photos and sondages indicated that a Roman camp in the shape of a playing card was established partly above the ruined Temple and partly to its west, perhaps as a temporary encampment in the mid- to late-third century (3 coins) and then as a more permanent structure during the fourth century (19 coins).

In the Byzantine period Christian solitaries established themselves in several caves and there is evidence of at least one pilgrimage site at a holy-man’s tomb and a reliquary for pilgrims to gather holy oil.

Whilst dropped coins indicate that the jebel continued to be visited over the centuries, there is no evidence of any further occupation.

Excavation history

Graeme Clarke detected traces of the fortress town of Jebel Khalid in 1984 while conducting a survey for a University of Melbourne team of archaeologists who were excavating the Bronze Age site of el-Qitar about 3 k upriver:

I came across some pottery pieces, which eventually led me to the remnants of a city wall, and I realised what I had found.”

With the permission of Syrian archaeological authorities, and with Peter Connor as co-director, survey and mapping of the site was carried out in 1984-1985. In 1986-1987 the fortifications were documented and five sondages opened. Excavation seasons, usually of about two months, were conducted in 1988-1991, 1993, 1995-1996, 2000-2002, 2005-2006, 2008, 2010, with some study seasons in between. Sadly, Peter Connor passed away in 1996; Heather Jackson became co-director in 2000 and John Tidmarsh in 2006.

Excavation trenches are clearly visible on Google Earth and Bing Maps (Latitude 36°21'38.21"N, longitude 38°10'23.64"E):

A season team might involve an illustrator, a photographer, a conservator, an architect, a surveyor, metal, glass and coin experts and a botanist, along with 15-18 others, many of them student volunteers. Over the years, some 69 people have acted as trench supervisors. Up to 100 locals have been employed at the site at any one time. Details of personnel and funding are listed here. This website also has copies of the excavation Field Books and the Inventory Books of objects found.

Careful excavation takes time. It took eighteen year (1988-2006) to fully excavate one block of houses, with more than 100 rooms and courtyards.

In 2010 work was continued in Area S (Commercial? Area), the Acropolis, the Temple, and Area X. Since then it has not been possible to return because of the situation in Syria. The Syrian government reported illegal digging at the site in 2014.

Some artefacts found at the site were deposited with the National Museum of Aleppo. Others were in storage in the village of Abu Qalqal. The present fate of these objects is unknown.

The Australian Mission to Jebel Khalid has produced six major reports, with another in press, and more than one hundred and fifty other publications.

The Australian Mission to Jebel Khalid is a joint project of the

Australian National University and the University of Melbourne.